When we say that art is alive, we typically mean it in a metaphorical sense. We mean it has realism which makes it’s depicted figures seem alive, or that it recalls memories or sparks political debates which are all very much alive and have weight and power in our world. But the Mayan ruler Lord Pakal II’s sarcophagus lid was viewed by its contemporaries as alive in the most human of senses.

It’s style isn’t ‘realistic’ as following that European tradition, nor does the stone suggest any vitality, instead this sense of being alive is in it’s purpose. This was one of politics and interaction, but, most importantly, of manifestation. In fact, it was meant to manifest the continuing of the world, the very preservation of all that was and would be alive. It provided it’s owner a physical form for his soul as he would venture on a quest to rejuvenate the universe, as well as being seen as a vital entity in and of itself.

Pakal was the Lord over Palenque from around 615 to 683 CE, in what is commonly seen as the “golden age” of the city. But, just as we see the Renaissance as supposed the height of culture and all that is good, it can be argued that this was a self-declared title- the result of a carefully curated image through cultural means. Art as a manifestation of power, both material and political, is a concept universal to all cultures. A literal manifestation of wealth through materials, but also the preservation of a figure’s image to extend their power beyond their death. Pakal, well aware of both these uses of art, actually erected most of the buildings in Palenque during his lifetime, a testament to the economic power and political strength he held. He always ordered the design of his own tomb, displaying it in his pre-made burial house before he had even died. He was able to declare his authority in his lifetime and after his death, justifying his own son’s claim to the throne. In short, this was the creation of a legacy.

This political power was also one of spiritual authority. You see, Mayan rulers were seen as bridging the connection between the earthly and spiritual realms, a role that is the exaggerated kin to the ‘Divine Right of Kings’ which plagued Britain and the like in centuries past. But rather than simply using this connection as justification for high status, Mayan rulers were seen as playing an essential role in literally continuing time. As despite on the sarcophagus lid which he was to be laid under, Pakal was to travel to the underworld, Xibalba, and then to ascend into the heavens and take his rightful place among the gods. And it was this heroic journey that would allow the continuance of time in the face of otherworldly threat. But more on this later, for now we will focus on the political influence of such a narrative.

Such a narrative is persuasive, especially for an audience on the brink of the chaos bought on by the end of a rulers life and the end of a period of stability, both political and spiritual. The end was night, and only Pakal could save them.

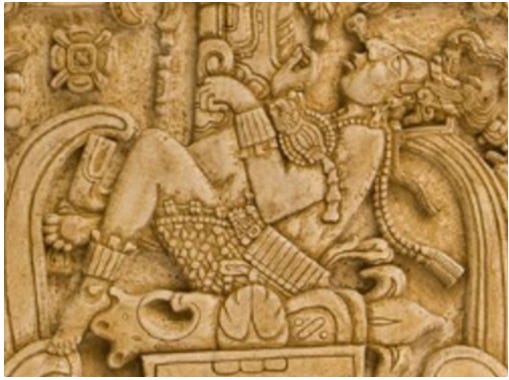

His god-like control over the metaphysical is seen in allusions to the gods throughout his tomb. This can be seen in one such panel which represents his wearing jewellery which linked him to the god of maize, Chac Xib Chaak. Maize’s symbolism was one of rejuvination and the circle of life, echoing Pakal’s journey was again. This was a visual language that would encode his power, laying it in stone for all to see, then and for centuries to come.

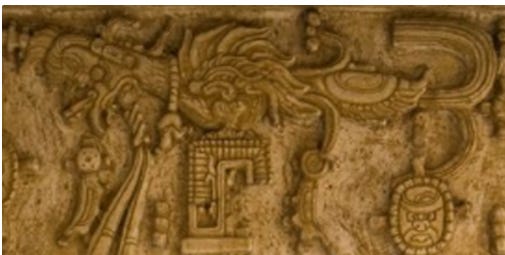

His and his lineages’ right to the throne was protected, in return for his heroic journey. Here, his posthumous ventures between would follow in the footsteps of the Hero twins, Hunahpu and Xbalanque, who had once ventured into Xibalba to defeat the lords of death. In order to do so, they had to sacrifice themselves, and thus allow themselves to be reborn in the celestial realm as the sun and the moon. Whilst the symbolism of the work is much debated, I think they can be seen in the upper area of the piece, the space reserved for the celestial realm, on either side of the central tree in the form of the two inhuman faces.

Pakal himself can be seen in the lower section of the work as he is reborn from the underworld, thus overcoming death. When I first started studying this work, I thought it was him falling into the underworld, as opposed to the idea that he is dancing out of Xibalba. I would argue that he is in fact in a more passive position, one of the “infantilized deity,” a foetal position as he is cradled by time itself. Further evidence against my initial idea, is in how his eyes are open, a motif commonly linked to the sun, thus suggesting rebirth after death, after night, and time’s general continuance after Pakal’s journey. He is being reborn as a god, just as time itself was being recreated after his journey.

He appears to be looking up at the heaven’s, specifically towards a bird seen in the branches of the central tree motif, and therefore among the heavens. Whilst it could be that the bird is simply a witness for the gods, I think it more likely that this is Pakal’s future form, when he is reborn in the celestial realm. Through it’s depiction, it could be manifested. Also, in Mayan imagery, birds were euphemistic of the penis, which could suggest procreative power, once again suggesting rebirth.

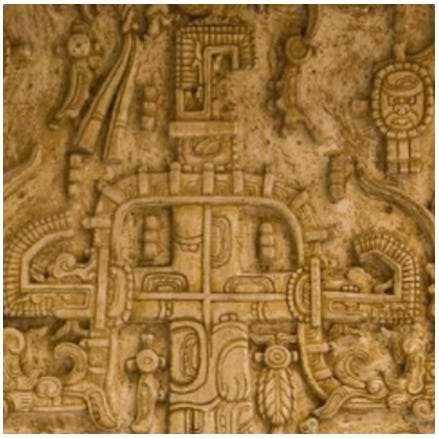

Now for this tree which I keep referencing and not explaining.

The symbolism of the tree here can be loosely translated to that of the ‘tree of life’: a symbol of vitality and connection between all things living and dead, seen in how it links the different sections of the work, from the upper celestial realm to the lower underworld of Xibalba. In this way, the destruction and the creation of life are connected, and Pakal’s journey down and then up the tree of life mirrors this cyclical belief.

Beyond the image, the work as a physical object also had meaning. Firstly, the Mayans conceived of the earthly realm as flat and rectangular, mirroring the form of the lid. This suggests that this object is a manifestation of the world, one maintained through Pakal’s sacrifice.

Furthermore, the sarcophagus lid was a vital being in and of itself, the result of how people interacted with it. This interaction is another reason why the sarcophagus was made before Pakal’s death, but it also took the form of, not just viewing the carving, but interacting with Pakal’s very body through the application of herbs and spices, and the subsequent mummification. There’s also the possibility of the ‘death dance’ being enacted sometime during the burial process. By treating it as active, as alive, the lid become so. Techniques of relief carving created this 3-dimensionality which places the image and who it depicts in physical reality, through having this tactile presence. In turn, this enabled the transfer of identity from that who it depicts into this new form- in this case, it is Pakal. No distinction between the depictions and the physical being were made in Mayan conceptualizations of personal identity. In this way, the image of Pakal was taken as a literal manifestation of him, as supported by view interaction. But also by his ‘soul,’ for want of a better word, to be read by it as instructions for Pakal’s journey.

In conclusion, the sarcophagus of Lord Pakal can be seen as defying ideas about what is ‘real’ and what is ‘art.’ This artefact is imbued with the purpose of manifesting the Mayan Lord’s journey beyond the grave and the subsequent order of time that it was meant to uphold. On a wider theme, this is an excellent case study in how art can illustrate culture’s philosophies and beliefs, their view on the world and the nature of life, and, most importantly, how art interacts and even reinforces this. In response to the constant battle art seems to be having to defend it’s very existence, the Mayan conception of art’s vital nature proves the argument against as futile. Maybe it’s time to view art again as upholding existence once more?

Questions to consider:

What are the lessons we can learn from the intersection between philosophy and art?

Is there anything you want to know more about Mayan art and philosophy?

Bibliography:

Bassie-Sweet, Karen. At the Edge of the World: Caves and Late Classic Maya World View. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996.

Coggins, Clemency Chase. “Classic Maya Metaphors of Death and Life.” The Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. 16, no. 16 (1988): 64–84.

Houston, Stephen, Stuart, David, Taube, Karl. The Memory of Bones: Body, Being, and Experience among the Classic Maya. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2021.

Laughton, Timothy. The Maya: Life, Myth and Art. London: Duncan Baird Publishers, 2003.

McLeod, Alexus. Philosophy of the Ancient Maya: Lords of Time. Lanham: The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, 2018.

Sanchez, Julia L. J. “Ancient Maya Royal Strategies: Creating Power and Identity through Art.” Ancient Mesoamerica 16, no. 2 (2005): 261–75.

Currently reading: The Dragon Republic by R. F. Kuang, Disability Aesthetics by Tobin Siebers

Currently listening to: Doctor! Doctor! by Zerobaseone, Oh Rosy by Milena, intro by Orion Sun, Perfume by Perfume

love this!