Paintings of women reading in suspicious abundance

An act of rebellion or domestic subordination?

In the expansive history of women being denied literacy, the abundance of paintings featuring women reading can seem like a rebellion, even if a quiet one. That is, until you realise that most of these are made by men. And that the amount is completely disproportionate to the percentage of the female population that could actually read.

I actually got the idea for this essay when looking for a new profile picture. Scrolling through the artworks, I noticed patterns in representation- the works fell into a few categories. There was also this artfully candid nature and hints at this voyeuristic act of watching these women read.

We need to understand what this activity is meant in the hands of women, literally. Especially when the paintbrush is in the hands of a man.

Are these paintings feminist?

At first, I was swayed between 2 reactions: firstly seeing their reading as a menial task, part of the everyday. Definitely nothing special. But I was also happy to see women reading throughout history, knowing how much literacy was restricted and demonised at times. To see a woman reading, as preserved in paint, felt like an act of defiance. This was, as I stated earlier, a rebellion, albeit a quiet one.

But both of these initial views can be seen as the result of my taking for granted the society I live in and its views of female literacy. It’s these modern views that permeate our view of the past and its this that led me to initially ignore a crucial fact: all these paintings were made by men. What we are looking at, therefore, is the male view of women reading.

Women’s subordination or a fight against it?

First it must be stated that something like this is never simple. Opinion on female literacy varied throughout history- period to period, person to person.

At some points, reading was seen as a perfect skill for a woman. But for the benefit of their husband. It was a marker of intelligence and ‘good breeding,’ therefore could make a woman more marketable in marriage by enabling her to make intelligent conversation in a polite society setting, thus showing her and her husbands’ cultured minds.

Reading also made the woman quiet. The passive figure, sitting in the domestic setting. Silent. Also a very sought-after attribute in a woman.

This scene from the 2005 Pride & Prejudice came to my mind. Elizabeth Bennet’s reading in a sitting room at Netherfield is interupted by a talk about female accomplishments. At Mr Darcy’s remark that “extensive reading” is what what makes a woman truly accomplished, she responds with: “I never saw such a woman. She would certainly be a fearsome thing to behold.”

“Fearsome” is a rather unexpected choice of words. This whole dialogue teeters between presenting reading as being a marketable hobby for a woman, but also an act of defiance against these desirable characteristics, thus making her “fearsome.”

This feeds into the argument that to read, was to go against a woman’s role. It was time spent away from domestic duties. It was a hobby for oneself, rather than for time dedicated to others.

To go against the set female role was associated with a colourful variety of effects on the body and even mind- in the most extremes, it was seen as leading to infertility. Rather than making them more marriageable, the very opposite was seen here. As for reading’s ill effects on the mind, we can turn to ‘The Yellow Wallpaper,’ where the main character is told to do absolutely nothing in order to mentally recover. Of course (spoiler), actually doing nothing makes her insane.

Reading was, therefore, viewed at some points as an ideal activity for women but, at other points, the very opposite. Either way female literacy was solely associated with desirability in the eyes of men.

Dangerous ideas and promiscuous actions

Another view on the matter was that reading would potentially introduce women to radical ideas which would further lead her astray from the home and from her husband. She might start questioning if she should have rights or, even worse, her own thoughts!

What was seen as even more shocking was the association of women’s independent thought with their independent pleasure. This can be seen in the euphemistisms that male writers treated the subject with.

Exhibit A

From Walt Whitman’s c. 1891 ‘So Long’:

“Camerado, this is no book,

Who touches this, touches a man,

(Is it night? Are we here alone?)

It is I you hold, and who holds you,

I spring from the pages into your arms…”

Exhibit B

Roland Barthes’ 1975 ‘The Pleasure of the Text,’ which draws links between the ‘body’ of the text and the ‘erotic body.’

As James Conlon says, “pleasure and wisdom are, literally, in her own hands.” This contrasts drastically with the idea of reading being a suitable hobby for the marriageable bride, with one school of thought associating it with rampant female sexuality and the other with respectable quietude- this contrast presents the Madonna/ Whore dichotomy. Yet both sides view the act of women reading as linked with solely with their desirability in the eyes of men, and both are equally represented in art.

Men like painting women reading

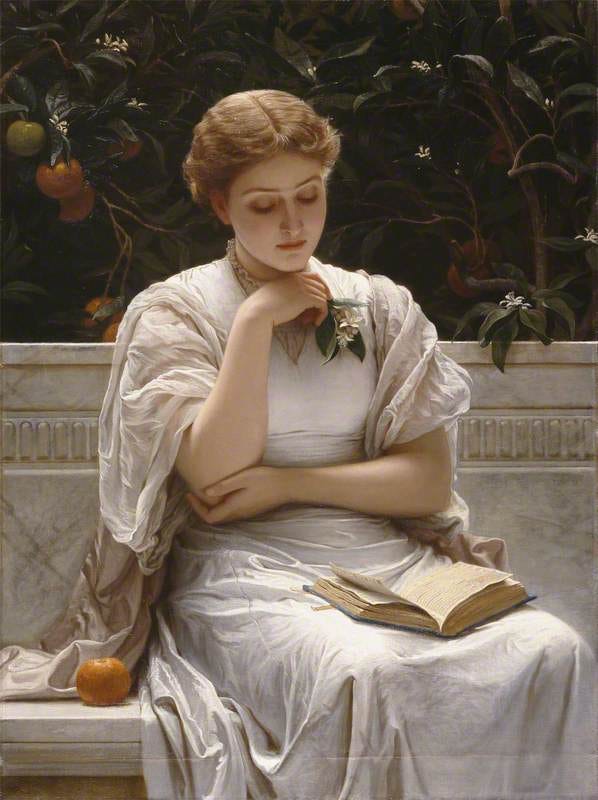

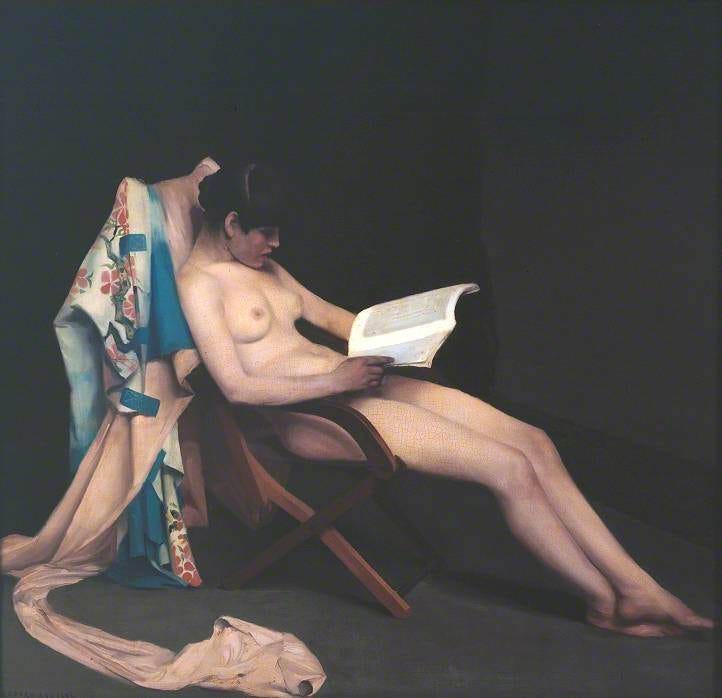

As a case study, we can see these opposing views on women reading in the following works:

These works, whilst both from the perspective of the male painter, present the reading female subject in contrasting manners. In Monet’s, reading is ‘rehabilated’ as a suitable subject for the respectable woman, whilst Roussel presents it is a euphemism for independent female pleasure. This is evident, first and foremost, in the perspective. We appear to be watching this woman, from the perspective of the painter, as she reads, naked. She appears oblivious to us looking on, absorbed in the book. This could be a nod to the euphemistic treatment of the female reader, an aspect ignored in prior interpretations of the piece. They also fail to pick up on the connotations of the kimono that is strewn across the back of that really uncomfortable looking chair. Whilst it can be analysed simply as a nod to the Japanese influences incoming to Europe, it can also be seen as representing exoticism: these newly incoming cultures, but also these incoming ideas of feminism, of the independent woman, both of which are fetishized. This takes away their potential radicalism, reducing it to objects of male desire.

One critic states that the book she is holding “becomes a tool with which she asserts her presence as not just a sight to be seen, but a force to be reckoned with,” completely overlooking the fact that it is a painting, one done by a man at that. It is a prop book and this is a model posed against a draped cloth background, painted at a time when men didn’t have such a good track record with the idea of female independence. Ultimately she is an object of the male gaze, painted as such for the assumed male viewer.

As for Monet’s piece, the latent sexuality equated with paintings of women reading is deliberately opposed. By placing the subject in a pastoral setting, Monet emphasizes the innocence of the figure, extending the symbolism of her white dress, and equates the scene with one of the past, before industrial cities and women getting ideas about having freedom of thought. I admit that it’s a beautiful painting, though.

Ultimately, these paintings’ polarising ideas of the female reader both agree that women should only be motivated by the desire of men. Views of female literacy shaped artistic depictions of such, hence how paintings of women reading are in abundance, providing another space for men to excercise their opinions. Women here are restricted to the role of the passive subject, a vessel for male views on their bodies, minds and desires.

Something so personal and menial as a hobby is presented as worthy of debate. We can’t look at painting simply to see a woman enjoying her own pursuits without having to consider why a man painted her like this and what opinion they were trying to project onto her. Menial everyday tasks are political acts in themselves, if not now or here, but elsewhere, in another time.

Questions for further discussion:

How does the present revival of reading interact with these debates of the past? Is it a continuation or in direct defiance?

How do female artists subvert the male gaze in their presentation of women reading? Consider the following:

How are these ideas changed by the positioning of the sitter? Is her back turned from the viewer? Is she facing them? Is she by a mirror?

Resources used and for further research:

James Conlon’s ‘Men Reading Women Reading: Interpreting Images of Women Readers’

Paula Rabinowitz’s ‘Scenes of Reading Women: Feminism and Paperbacks: A Possible Origin Story’ - note that contains spoilers for ‘Madame Bovary’ and, unfortunately, ‘Anna Karenina.’

Giano Scarvo’s ‘Pleasure, privacy and power: reading women throughout art history’

Currently reading: ‘Anna Karenina’ by Tolstoy

Random media recommendation: DIVA by After School

Hope you have a great week :)

Beautiful beautiful essay! I had always thought of the books in Monet’s pieces as being a prop of the rich, but it unfortunately makes much more sense that it’s just another medium for women to be objectified :/ I’d be interested to see how women reading are portrayed in paintings around the world too, and if the artists see women in the same way!

Whew! Thank you for Cassatt’s paintings, which come as a relief after those nudes. Good grief, guys!